NOTE: This essay was originally written in July/August 2022.

A little over a year ago, I wrote Playing Different Games1. The piece was my attempt at explaining the tsunami-like phenomenon that was Tiger Global in the scorching hot venture/growth2 market of 2020 & 2021. The TL;DR was that:

Most people thought Tiger was crazy and/or stupid for its aggressive + high velocity investing approach

There was, in fact, a method to Tiger’s madness which involved breaking many outdated/imaginary rules of how venture capital should be practiced

Tiger’s strategy created the first structural, non-brand driven competitive advantage at scale in venture, which would enable it to generate more $ returns than competitors & capture increasing market share3 over time

How is that thesis working out a year+ later? In meme parlance, let’s just say…

How it started:

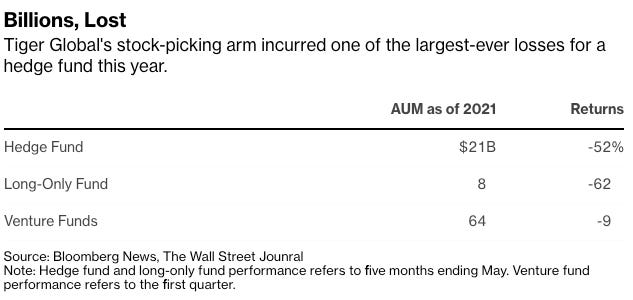

How it’s going:

Wellllllll, sh*t.

As anyone with a pulse and access to the internet knows, it has been QUITE. A. YEAR. since Playing Different Games was published. We’ve just witnessed the worst crash in tech/high-growth company valuations since the dot-com crisis, and no one has been rocked harder by this bubble bursting than Tiger Global & its tech crossover fund brethren4.

So how does the guy that wrote the memo on Tiger feel now that they’re the poster child of the biggest tech crash since the dot-com bubble? The short & unsatisfying answer is “It’s complicated!” My longer answer follows in what Substack tells me is about a 20-minute read.

Playing Different Games offered up a framework for the future of venture which, in hindsight, was incomplete. It ignored the potential for changes in the market environment as drastic as we’ve experienced in 2022, and subsequently became stale far sooner than I was expecting. The silver lining? My piece’s early obsolescence forced me to zoom out & broaden my perspective on the future of the industry, and when I did I saw something even bigger than Tiger on venture’s horizon.

In the fullness of time we’ll see Tiger’s dominance in 2020 & 2021 as a harbinger of things to come in venture; a first glance at the power of a large fund using its scale to create competitive advantages. It won’t be Tiger who leverages this idea to its fullest, though. In coming years we’ll witness new Venture Platforms emerge that weaponize their scale to outcompete competitors and capture market share in a more durable & resilient way than Tiger. Over the long-term these funds will be as disruptive to the asset class as Tiger was in the short-term, and with the right context I think it’s clear why.

Game Over?

I began the conclusion section of Playing Different Games by summarizing the key to Tiger’s success:

Tiger identified several rules / norms / commonly held ideas in venture/growth that are stale & outdated and built a strategy to exploit the contemporary realities around those ideas at scale.

Tiger had a unique product, which I called Better Faster Cheaper (B.F.C.) Capital, which enabled a unique approach, which I called Maximum Deployment Velocity. In an environment where

Founders were fed up with unhelpful VCs & exasperating fundraises, and

LPs were hungry for more venture/growth exposure due to a decade+ of strong returns in tech, falling interest rates / capital abundance, and an unprecedented acceleration of digital businesses post-Covid

B.F.C. Capital and Maximum Deployment Velocity were a comically unstoppable combo that led to a pace of capital deployment that venture had never seen in its history.

Others got in on the fun too — while Tiger was certainly this bull market’s main protagonist5, there were a colorful cast of supporting characters finding ways to play in tech’s fastest & biggest rally since 1999:

Redditors formed an online army that very successively manipulated the price of stonks and caused billions of dollars in losses for hedge funds

The whole SPAC thing happened and some charlatans made gobs of money taking companies public that had absolutely no business being public

Crypto investors told the world to have fun staying poor while they sold JPEGs of apes for >$1M a pop and prices of assets like Solana rose from <$1 pre-Covid to $260 in November 2021

Now that we’re in more sober times, it feels surreal looking back on it all. Put bluntly, sh*t got weird.

In the short-term, the increasing level of tech mania in ‘20 & ‘21 acted as an accelerant to Tiger’s B.F.C.C.<>M.D.V. flywheel: as the joking mantra “stocks only go up” became an actuality for tech-related assets month-after-month-after-month, Tiger provided Founders and LPs alike the best way to get in on the action.

At the same time, the snowballing frenzy ballooned the size & scope of the market’s inevitable crash back to earth. When the tech market apocalypse did eventually come, it broke Tiger’s flywheel like it was an actual wheel made of toothpicks and papier-mâché, and Tiger along with it.

That’s not to say that Tiger is the only fund who has been laid waste to by 2022, far from it! There are many funds out there - crossover and pure venture/growth alike - whose managers lie awake at night on their Eight Sleep mattresses regretting the investments they made in ‘20 & ‘21, and you’ll be hard-pressed to find many funds that are thrilled with how that vintage of investments pans out when all’s said and done6. But Tiger went the biggest, and Tiger stretched the furthest. While it’ll take years for us to actually know how its recent vintage of private investments turned out7, odds are it won’t be pretty.

To be fair to my past self, I said explicitly in Playing Different Games that Tiger’s continued performance was contingent “barring a dot-com-bubble-like crash”8, and purposefully avoided predictions on where the tech market was going to go returns-wise. That still leaves Playing Different Games as an incomplete analysis, while it purported to be a holistic look at the future of venture. I didn’t account for how this product and approach would perform in a diametrically opposite market environment to what venture experienced for a decade+ preceding 20229.

Welp, that environment is here! And after many long mornings of coffee and contemplation, I think there’s a lot to learn from Tiger’s fall from grace, starting with its notorious attributes.

Venture Attributes

In Fall 2021, if you asked a startup founder to describe Tiger Global, what would they tell you? Would they say “Well, Tiger Global is a tech-focused investment fund based in New York that focuses on internet, software, consumer, and financial technology industries.”? Hell no!

The first thing out of the founder’s mouth would be words like Speed. Aggressive. High prices. Hands-off approach. Bain. You’d probably get an anecdote10 about a fundraise process that the founder heard about where Tiger offered to lead a round within 30 minutes of a first phone call, said with juuust a hint of wonder and mystique in their tone.

As it became the only fund that anyone could talk about, Tiger stopped being a hedge fund. Tiger was B.F.C. Capital. Tiger was Maximum Deployment Velocity. Tiger defined this new product and approach, and in turn they defined Tiger.

Ultimately, this is what venture firms are: sets/configurations of attributes that founders believe will increase their probability of success and LPs believe will produce above benchmark returns11. The more compelling a firm’s attributes for a given founder at a given point in time, the more likely the founder will choose that firm as their investor over its peers.

Tiger developed notoriety for spiking massively on a small subset of attributes: high velocity, speedy diligence/process, high valuations, light-touch involvement, access to high-quality consulting services. Short & sweet! For a long time this narrow depiction worked in Tiger’s favor; it created a simple value proposition for founders that was easy to grok, highly differentiated, and a perfect fit for the prevailing market environment.

The problem with being strongly defined by a narrow group of attributes is that in a sea change event, your attributes can end up going from extremely in-vogue, to almost entirely out-of-vogue, with little room to maneuver/pivot.

This is the problem El Tigre faces today beyond the performance of its historical investments — B.F.C. Capital and Maximum Deployment Velocity (and their resulting attributes) are all but incompatible with this new market environment. When a 50%+ market correction hits:

“High velocity” venture/growth investing becomes impossible as the gap between public & private valuation multiples widens and becomes untenable

The adverse selection problem associated with being known for “speedy, light diligence” gets 10x worse as startups rush to raise from you as their prospects worsen

Portfolio founders raise downrounds and regret previously raising at a high / stretched valuation due to the impact a downround has on employee morale

Tiger can’t continue its strategy as-is in the current market environment, but without B.F.C.C. & M.D.V., what is Tiger?

Ironically, this isn’t a problem for most funds because their attributes are about as bland and undifferentiated as JCPenney’s selection of on-sale men’s wear. In Playing Different Games, I claimed this lack of differentiation was due to complacency on the part of those JCPenney VCs. While that’s still absolutely true, I believe it also stems from those funds’ lack of understanding about a critical aspect of venture that Tiger understood very well: that most venture attributes stem from components that are commodities12 and/or benefit massively from returns to scale.

This is where things get interesting, because the subsequent implication is that the venture industry is susceptible to economies of scale as a source of competitive differentiation. I didn’t frame it this way, but my description of Tiger’s flywheel in Playing Different Games was essentially a description of its successful use of scale to drive competitive advantage. Scale benefited Tiger’s

Cost of capital — by enabling the trade-off between lower deal-by-deal returns in exchange for a faster pace of capital deployment13.

& Decision speed — by enabling them to pay big $$ for Bain to buttress research/evaluation efforts

But couldn’t a fund improve other attributes with scale if it wanted to? Could it improve.. all of them?

In Playing Different Games I used analogies like Walmart to describe fast & cheap capital, Tiffany & Co to describe fancy & expensive capital, and of course JCPenney to describe capital that is neither cheap nor fancy. There’s one analogy I didn’t think of at the time but absolutely should have in hindsight: Amazon Web Services, colloquially known as AWS.

Venture’s AWS Moment

For the uninitiated14, AWS is not only Amazon’s crown jewel, it’s also one of the most important businesses in the world. At a high level15, AWS:

Buys massive quantities of commodity computing components like servers, networking equipment, data centers to house the servers/equipment, etc.

Builds out computing “primitives” (e.g. file storage) using these components

Sells access to these primitives to developers

Businesses - ranging from individual passion projects to the largest companies in the world - depend on AWS’ infrastructure when building their digital products.

In his piece The Amazon Tax, Ben Thompson introduces a very helpful graphic to understand AWS and what makes it special from a business perspective:

The “primitives” model modularized Amazon’s infrastructure, effectively transforming raw data center components into storage, computing, databases, etc. which could be used on an ad-hoc basis not only by Amazon’s internal teams but also outside developers:

Ben illustrates that AWS is defined by high fixed costs and returns to scale. Amazon spends $10s of billions a year to 1) build new and 2) maintain existing infrastructure. The more they spend/build out, the more cost efficient it becomes to build or maintain a single server/unit of infrastructure16. That’s returns to scale. And spending $10s of billions per year just to maintain their infrastructure every year generates barriers to entry which protect against potential competition. That’s high fixed costs.

Using the cost advantages provided by its scale, AWS implements a scale economies shared (SES) strategy, defined as “when a company benefitting from economies of scale chooses to lower its prices and/or improve its offerings to customers in order to win market share over the long-term, rather than pricing its products to maximize per-unit profit in the short-term.” (Source) To illustrate what this means in practice, in 2021 AWS announced that it had reduced prices 107 times (!) since it was launched in 2006. How much would you love your landlord if they lowered the price of your rent 107 times17?

Now, if we were to ~VC-ify~ Ben’s graphic, it might look something like this:

Taking the analogy even further, we can take this snippet from Brad Stone’s The Everything Store on why Bezos settled on the idea of “primitives” for AWS, and see if it translates to this framework for venture:

If Amazon wanted to stimulate creativity among its developers, it shouldn’t try to guess what kind of services they might want; such guesses would be based on patterns of the past. Instead, it should be creating primitives — the building blocks of computing — and then getting out of the way. In other words, it needed to break its infrastructure down into the smallest, simplest atomic components and allow developers to freely access them with as much flexibility as possible.

Turns out we can ~VC-ify~ this too! (please don’t hate me Brad):

If Venture Fund X wanted to maximize the probability of success among its startup founders, it shouldn’t try to guess what kind of services they might want; such guesses would be based on patterns of the past. Instead, it should be creating primitives — the building blocks of a founder<>investor relationship — and then getting out of the way. In other words, it needed to break its offering down into the smallest, simplest atomic components and allow startup founders to freely access them with as much flexibility as possible.

It may read like the lamest version of Mad Libs ever, but it translates surprisingly well into a pitch that would be compelling for many founders. In an ideal world, wouldn’t venture funds act for founders as AWS does for developers? Providing the most cost effective18 attributes/venture products to startup founders possible, in whatever configuration & scale they preferred?

Now, the obvious problem here is that most venture “components” are or are driven by people. People aren’t servers (yet), and hiring a million of them doesn’t make them drastically cheaper on a per-person basis, so this is by no means a perfect analogy. What matters, though, is that like AWS, nearly every aspect of a venture fund can be 1) modularized and 2) improved massively with scale. And that’s a huge deal.

Money — an actual, literal commodity — is an easy example of this, and Tiger “improved” this commodity with scale by trading higher investment velocity for lower by-deal returns. But it’s hard to think of a venture “component” that can’t be improved with scale:

With scale you can invest to create a bona fide media empire

With scale you can afford to hire the best tech execs in the world to join startup boards

With scale you can pay consultants $100M+/year to support research & diligence efforts

With scale you can hire an army of analysts/associates to ensure maximum sourcing coverage

Traditionally, the venture business has been categorized as having very little fixed costs19, and the prevailing wisdom has been that "venture doesn’t scale”. If an investment firm could flip these on their head — by operating with meaningful fixed costs20 and sharing the returns of their scale with its startup founders — it could introduce a source of structural/durable competitive advantage where hadn’t existed prior.

Tiger had large scale, significant fixed costs (e.g. annual Bain bill), and did share the returns of their scale with founders (by reducing their expected by-deal returns / increasing valuations). The problem is that this reinvestment was too lopsided. Tiger focused entirely on a small subset of attributes that had incredible product-market fit in an environment that didn’t last, at the expense of building a more resilient foundation to better weather a storm, much less the hurricane that has been 2022.

Don’t feel too bad for the folks over at Tiger though. They raised and deployed more money in private markets 2020-2021 than they had cumulatively from the inception of the firm up to 2020. On fees alone the partners there are going to be very, very, ridiculously rich. But by scaling in the way they did, it does feel like they failed the marshmallow test for a greater prize. Tiger traded a one-time generational opportunity post-Covid to raise/deploy a massive sum of capital, for a decades-long opportunity to be the AWS of venture/growth.

Over the next decade, we’ll witness venture/growth market share aggregate at an increasing level to a few funds leverage the power of scale strategically by reinvesting heavily into their “modular components” as they scale. These funds — which I’ll call Venture Platforms — will create compounding competitive advantages that apply through market cycles, and enable them to outcompete & outgrow competitors. But where else can funds leverage the power of scale? And why hasn’t every large fund already done this?

Venture Platform Creation

Many large funds — which I’ll roughly/mostly arbitrarily define as having $25B+ in AUM — exist and have for years. Most of these funds haven’t and won’t leverage the power of scale to become compounding venture platforms. In fact, most are as undifferentiated and uninteresting as any other generic fund, small or large (and they’ll stay that way).

The key to establishing a venture platform — and what most large funds lack — is the combination of:

Modular venture org design — which maximizes returns to scale for venture components

Meaningful + strategic platform reinvestment — which acts as the fuel for a scale economies shared strategy

Benevolent + ambitious dictators at the helm — who can maintain the strategy long-term and manage the natural human-related issues that arise within orgs

I’ve described each of these platform elements in more depth in “Appendix I — Venture Platform Elements”, which I’ve moved down there for the sake of the flow of the piece.

For funds that nail this trifecta, their resulting platforms will look something like this:

These funds will work to make various commodity components into basic prerequisites that founders expect when working with venture/growth funds. When pitching to founders they’ll be able to say things like:

Need to hire an exec recruiting firm to hire a new c-suite exec? We have the #1 rated firm in tech on retainer and their services are 50% off for you because of our large annual retainer fee.

Want to know exactly how you stack rank vs. every other business in your general sector? We’ve spent millions on a database that tracks every public and private business as they’ve grown from seed-to-public company and give you access.

Want advice from other great founders instead of VCs? Frank Slootman and Patrick Collison are in our founder WhatsApp group which you’ll be invited to once we invest.

If you don’t want any particular piece that I’ve laid out, that’s totally cool, just know those and much more are all there for you if/when you need them. You should expect this from any fund, shouldn’t you?

They’ll then invest heavily into a few areas of differentiation where the component isn’t as much of a commodity, but can still be improved immensely with scale. Again, pitching to founders, they can say:

“Given you’re a scaling SaaS startup about to enter your potential hypergrowth phase, the former CRO of ServiceNow will be your board member.”

Few if any other funds can give you this, can’t they?

Done poorly, this type of organization could become an unruly mess. The broad approach could create a lack of focus which makes defining the firm’s value prop to founders difficult. Or alternatively, it could suffer from its inherently large headcount via bureaucracy or internal conflict as partners jockey for economics, status, etc. But done well — with strong leadership at the helm keeping the firm focused & minimizing internal distractions/conflict — this type of platform is tough to compete with, and will only become tougher.

Brand — via ideology, exceptional track record, or just plain ~vibe~ — is seemingly the lone defense against the power of scale. having a distinguished, durable brand is exceedingly rare21. Over the last decade+ venture has transitioned from the art of backing contrarian moonshots to a game of mimetically piggybacking on consensus favorite companies as they break out22. This mimetic strategy has rubbed off on the venture firms themselves and has them looking more similar to each other than ever before. They have offices in the same places, they wear the same Patagonia vests, they drink the same coffee23 — a good portion of the industry has basically morphed into an amorphous blob wearing a Stanford hat. That leaves scale as the lone option for these firms to develop differentiation, and without it, they’re left without a defense against the largest firms that will inevitably wield that scale as a competitive weapon.

At an asset class level, the emergence of these venture platforms signals venture/growth’s entrance into its asset accumulation phase, it and every other asset class’s end game.

Venture’s Endgame

Categories in which players benefit from scale economies trend toward consolidation, and venture is no different. Tiger may not be the fund that ends up accumulating the most assets, but it will still happen, and it will be done by just a few funds.

Remember, we’re talking about market share of capital deployed, not “best returns” or anything like that

Returns for these firms will likely be lower, and they will drag down the returns of other players too

This is good for founders on net and good for anyone creating equity vs. buying it

Share of AUM will increasingly accumulate over time to AWS-like venture platforms that reinvest heavily into their own capabilities & raise the cost of competition for others. These funds will also drive overall AUM growth in venture over the next decade. This isn’t necessarily an ideal outcome for venture, but it is the logical one, and one that mirrors the evolution of many assets classes before it.

Once Pandora’s Box has been opened, there is unfortunately no way of going back — venture/growth is not going back to the cottage industry it once was, and we have very likely entered the “asset accumulation” phase of the industry. Generally, as an asset class institutionalizes and AUM trends toward its natural upper asymptote, returns erode and trend towards beta. This point is illustrated well in Minsky Moments in Venture Capital by Abraham Thomas, who describes how this played out in the bond trading markets with this graphic:

What’s interesting about VC vs. markets like Bonds or Real Estate - it’s much much smaller. What’s the upper asymptote on the amount of capital that can be deployed productively in private venture/growth markets? I’m not sure, but I have a feeling we’re going to find out over the next few years.

This isn’t to say that some funds won’t be able to still create incredible, 10x funds in the future. If you want alpha, stay small, and pick something you’re extremely good at. Warren Buffett once said if he ran a $100M fund, he’d be able to double it every year. You can still very much do that in venture! Funds like Cyberstarts and Amplify are proving this out in real time. But if you want to buy the most expensive house in California? Get big, and begin reinvesting in your platform.

This trend & its implications brings to light some existential questions that investors need to be thinking about right now:

What is the upper asymptote on capital deployment per year in venture/growth?

What comparative advantage does my firm have? Should we stay smaller/focused or should we begin investing in platform?

For those that stay small, what is the best way to insulate against the growing power of platforms?

For those that become platforms, what is the best way to keep your firm from becoming a bureaucratic mess?

Many of the very best investors will exist outside of these platforms and will still generate amazing returns, but on net more will be sucked into the gravitational pull of platforms.

To review this specific exploration of the future of venture:

The worst tech crash since the dot-com crisis broke Tiger’s B.F.C.C.<>M.D.V. flywheel and left it in a precarious position — Tiger failed the pandemic cycle’s “marshmallow test”, and while they are back to investing in privates, the brand/reputational damage is likely durable.

Other Venture Platforms will emerge in the near future that leverage the power of scale in venture/growth — The trend that Tiger pursued is secular; they showed that we were not at the efficiency frontier of capital deployed in the venture/growth ecosystem, and platforms are emerging that will test the limits of this frontier.

Venture/growth market share will increasingly accrue to these Platforms, and venture will fully enter its “asset accumulation” phase — We are entering venture’s asset accumulation phase, which means increased asset class AUM (aggregated primarily by venture platforms) at the expense of MoM returns. This happens to every asset class as it becomes more institutionalized, and venture is no different.

This is a long-term game, those that plan for the long-term will be rewarded, even if it means that there’s less to go around for those that don’t.

Appendix I — Venture Platform Creation

Modular Venture Org Design

Software is eating the world, and venture firms are no exception. Specifically, the evolution of large venture funds over the past few decades looks a lot like the evolution that software application development took from monoliths to microservices.

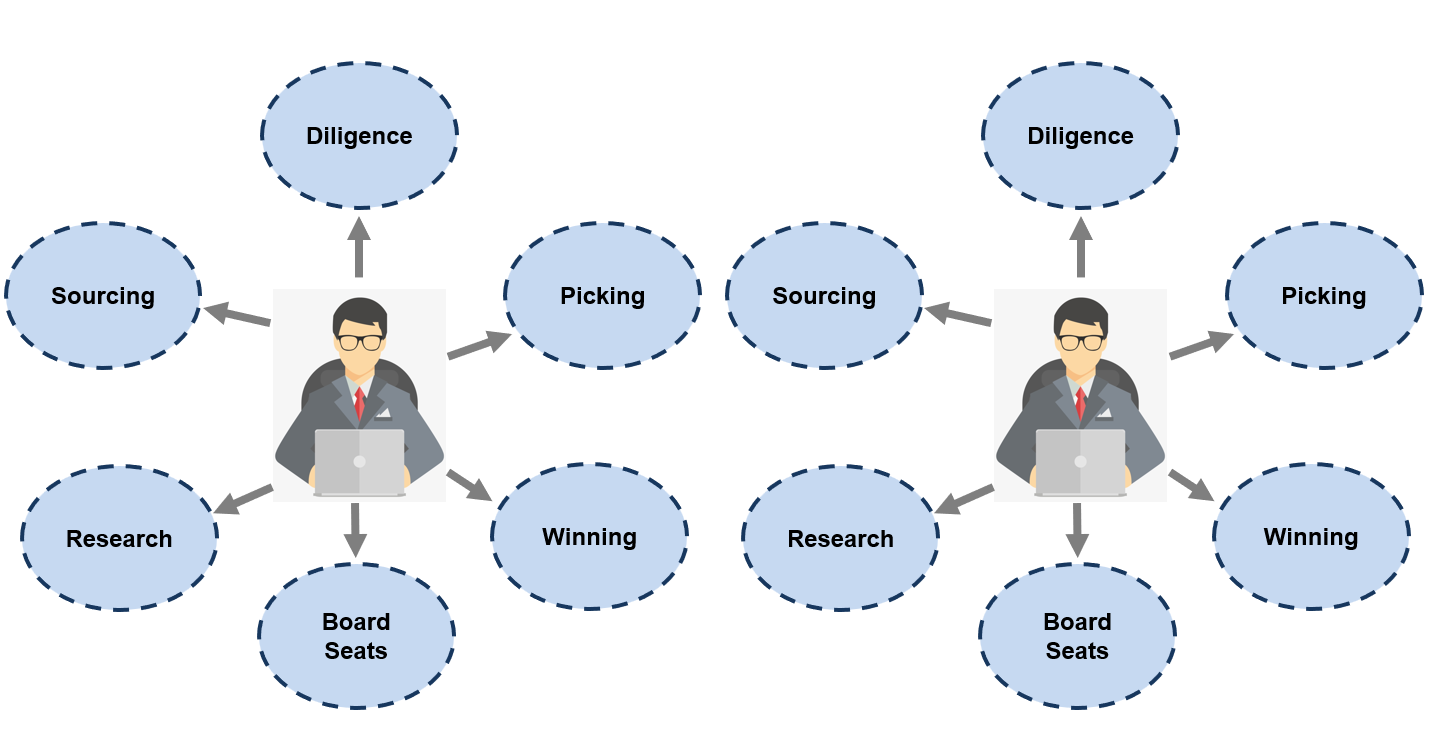

Historically, VC firms were built essentially as small monoliths. Each partner at the firm was tasked with finding investments, evaluating/picking investments, winning investments, sitting on boards, helping the companies where they could, etc. A traditional venture firm was essentially 6-10 separate monolithic applications residing under the same roof.

This is one of the key reasons why people say “venture doesn’t scale”. With this org structure, once a partner is deeply involved with/on the board of a dozen different portfolio companies, their productivity dives as they get bogged down with ongoing portfolio duties at the expense of finding new investments and staying in the venture “info flow” to find the next big thing.

As the asset class (& its funds) have grown, many of the larger/growing firms have evolved their org structure to better handle their increasing scale, and they now more closely resemble microservices architecture. Instead of having all-in-one partners, a firm breaks down each of its function/processes into its modular parts and hires people/invests in resources that are the most effective at that function24. Division of labor at its finest!

This modular org design creates a few substantial benefits relative to a monolithic design:

A fund can hire people that are best-in-class in each fund function (whereas all-in-one partners are likely lacking in one or multiple areas)

Fund functions can more interchangeably be served by internal OR external resources

A fund can create much more unique combinations of attributes based on what a specific investment calls for (vs. a single partner representing most/all attributes associated with the fund)

A fund can replace people that underperform more easily

If bottlenecks arise in any given fund function, a fund can scale up resources for that function specifically

Private Equity (meaning LBO) firms, which as a category reached scale many years before venture grew out of being a cottage industry, have been run with this org structure for many, many years given its scalability (beyond scale, there’s also more analysis/process work done in PE than in VC which necessitates larger teams & this org design’s scalability).

Many of the great, historic venture firms of history were built as small partnerships/monoliths, and many extremely high quality partnerships will continue to thrive for as long as venture exists. There will also always be software applications built as monoliths, but the largest, robust applications are built via microservices — the same will be true of venture/growth funds.

This is far from the whole story when it comes to making a venture platform, though. Plenty of venture/growth funds have had this org structure for years, and while its helped them manage scale, it hasn’t created differentiation. Differentiation comes when each fund function is better than the competitions due to the people & resources invested in it. That takes thoughtful thoughtful & substantial platform reinvestment.

Meaningful Platform Reinvestment

Venture funds make their money from two sources: management fees (usually a 2% fee on the size of an active fund, per year), and carried interest (usually a 20% share of the distributions/profits funds generate after an investment exits). This is a very simplified explanation of fund economics, and if you’re curious for a deeper dive see here.

The purpose of management fees is to pay for a firm’s operating expenses (OpEx), things like rent, investor & other employee salaries, software, etc. Carried interest — which if a fund is successful generates far more $$$ than management fees — typically goes straight to the pockets of a firm’s GPs.

As you’ve probably surmised, a fund’s capabilities/components are OpEx items, and are funded by the fund’s management fees.

The overall flow of money through a venture firm usually looks something like this:

Historically this has worked just dandy — venture is a low fixed cost business and fees are more than enough to cover rent, salaries, and a few team building offsites to Napa. Firms kept opex low and if they were good enough (and lucky enough) to generate real returns, GPs with carry in the fund would enjoy the spoils entirely.

Now, there’s no rule saying that venture firms have to keep their fund OpEx low, or how they have to fund their OpEx. If a firm chose to, they could invest not only all of their management fees, but a portion (or all) of their carry back into the fund’s OpEx to improve their fund’s offering!

Tiger was actually a great example of this — Tiger’s GPs reinvested carry into their fund quite literally by becoming the largest LP in each of their new private funds. By being the largest single LP in each subsequent fund, Tiger’s GPs gave their LPs more confidence that they were aligned to generate strong returns. While they may or may not regret doing so in hindsight, this was a smart and effective example of platform reinvestment that enabled increase deployment velocity (as was their strategy).

The problem with platform reinvestment is that oftentimes partnership dynamics at a fund prevent any real reinvestment from happening. To see real, long-term reinvestment back into a venture platform, you need a benevolent dictator (or two) at the helm.

Benevolent, Ambitious Dictators

With a typical venture partnership model, GPs/Partners within a fund split up a fund’s carried interest. Sometimes the splits are equal, more often they’re not, but generally the economics and decision-making power within a firm is split among anywhere from 4-20+ people.

This partnership model is often incompatible with long-term, substantial reinvestment back into a venture funds offering. When there are various decision makers with power over the strategic direction of a firm, you have many more opportunities for disagreement about 1) how much the partnership should be investing back into its capabilities, as well as 2) the priority of those investments.

A second problem that plagues partnerships is a lack of world-conquering ambition. In fact, a lot of the problems that venture funds run into in the long-term have to do with how much damn money the funds, and subsequently their GPs, make if they see success (with problems like these who needs solutions, ammiright?). If a 5 GP partnership 5x’s a $500M fund, that’s $80M of pre-tax carry to split between those 5 GPs. Multiply that by a few funds and you already have more money than most could spend in a lifetime. This leaves many GPs unmotivated not only to continue to compete at a high level, but even to do basic things like succession planning and ensuring the continuation of their franchise.

A single head decision maker (or duo of decision makers) that own the lion’s share of the economics and power within a firm can more easily decide to heavily invest for the long-term. These single or duo led leadership teams also tend to have more ambitious visions, and are gunning for top spots on the Forbes Billionaires List rather than “just” settle for f*ck you money. And the path to that level of success ends with $50B+ AUM.

If you haven’t read that piece yet, this one will make a lot more sense if you do.

I am going to use the terms “venture” and “venture/growth” interchangeably throughout this piece. By venture or venture/growth, I am specifically referring to Seed through Pre-IPO investments in tech & tech-related businesses. Most relevant to crossovers like Tiger Global is Series B through Pre IPO, though impacts on this portion of the asset class impact Seed & Series A as well.

By “market share” I roughly mean the % share of $ invested in the venture/growth asset class over a year or other given time period

A ton of great material has been written summarizing this most recent tech market boom and bust, its causes, etc., so I won’t be addressing / rehashing all of that here. If you aren’t up to speed, my favorites in this genre include: Bull Market Rhymes, Minsky Moments in VC, and Reversion to the Mean: the real Long Covid. And if you don’t have time to read those, the SparkNotes version of the last 2 years goes something like this:

“Oh no Covid stop economy! Powell money printer go brrrrr to help economy. Now people stuck inside with money and nothing to do. People buy things online. Businesses do DIGITAL. TRANSFORMATION. People download gambling stock trading apps & form Reddit army. Army buys Stonks. Stonks go up. Money printer still going brrrrr. Stonks only go up? STONKS ONLY GO UP. DOG COINS ONLY GO UP. GABE PLOTKIN BAD. EVERYONE IS RICH. Everything is more expensive. Everything is more expensive? Inflation! Fed moves up rates to slow inflation. Inflation not stopping? Uh oh! Stonks going down! Inflation not stopping!! Rates not stopping!! AHHH—” *screen cuts Soprano’s style*

Or antagonist of course, if you were having to compete with them.

I said as much in Playing Different Games — from the Appendix: “If a big crash happens, every market participant will be impacted, and LPs will likely not like the way the vintage pans out whether you are Tiger or not.”

Ironically Tiger’s private book is massively “outperforming” its public book for now, an issue that is covered masterfully in Rajan Roy’s Late Stage Prisoners Dilemma

In “Appendix II - On Market Returns”

Looking back, Tiger probably could’ve started this strategy in 2012 and seen similar success for a full decade (albeit at smaller scale)

More anecdotes on this Twitter thread for those curious

If you remember from Playing Different Games, these are the two immutable rules of venture! You have to produce minimally acceptable returns such that LPs will keep investing in your funds, and you must have a product that founders like enough to take your cash in return for equity in their companies (and those companies have to generate the returns that LPs are OK with, to complete the circle). There are no other rules!

A commodity, as defined by our friends (or is it enemies now?) at Wikipedia, is “a resource, that has full or substantial fungibility: that is, the market treats instances of the good as equivalent or nearly so with no regard to who produced them.” The money that VCs provide founders is the purest commodity that the industry deals in — the money itself is the same no matter who provides it, and all else equal founders would (generally) prefer more money for the % of their company they give to investors.

Tiger’s scale also helped them diversify more / reduce the chances that a few blow-ups would sink their whole portfolio (not that that helped all that much in hindsight), and enabled Tiger’s GPs to reinvest heavily as LPs into each of their new funds, which gave LPs more confidence / comfort in their high deployment strategy.

And by uninitiated I mean those that have been spared reading the dozens of tech thinkboi blog posts out there fawning over how great of a business AWS is & how much of a genius Bezos is for creating it… which is ironic because that’s exactly what I’m about to do

If you’re interested in a much deeper look at AWS, check out Justin Gage’s “AWS for the Rest of Us”

For example an OEM of servers will give you better per-unit prices if you spend $1B with them than if you spend $1M with them, and better still if you spend $10B instead of $1B!

Coincidentally that’s also the amount of times NYC landlords would need to lower prices in order for a 2BR apartment to become remotely affordable

“Cost effective” in this sense could mean the cheapest capital (i.e. highest valuation), but more often it would mean higher quality attributes for the same/similar price (i.e. investment valuation) as competition.

Well, okay a 10k sqft office lease on Sand Hill Road isn’t exactly “very little”

Assuming those costs are value generative for the fund’s capabilities

$1B Fund. 2% per year * 8 year fund life = $80M from fees. 20% carry * 5x gross fund = $800M. (Not including paying back management fees which funds usually do before they’re allowed to start taking carry)

Working at a fund that does have a distinguished brand is also a key reason I feel comfortable writing this piece

Nothing articulates this better than the Founders Fund Manifesto, What Happened to the Future?

Not a dunk on Cometeer I freaking love their coffee

Hello Everett,

I hope this communique finds you in a moment of stillness.

Have huge respect for your work and reflective pieces.

We’ve just opened the first door of something we’ve been quietly handcrafting for years—

A work not meant for everyone or mass-markets, but for reflection and memory.

Not designed to perform, but to endure.

It’s called The Silent Treasury.

A place where conciousness, truth and judgment is kept like firewood: dry, sacred, and meant for long winters.

Where trust, vision, patience, resilience and self-stewardship are treated as capital—more rare, perhaps, than liquidity itself.

This first piece speaks to a quiet truth we’ve long sat with:

Why many modern PE, VC, Hedge, Alt funds, SPAC, and rollups fracture before they truly root.

And what it means to build something meant to be left, not merely exited.

It’s not short. Or viral.

But it’s a multi-sensory experience and built to last.

And, if it speaks to something you’ve always known but rarely seen heartily expressed,

then perhaps this work belongs in your world.

The publication link is enclosed, should you wish to experience it.

https://helloin.substack.com/p/built-to-be-left?r=5i8pez

Warmly,

The Silent Treasury

A vault where wisdom echoes in stillness, and eternity breathes.